Disasters explained: floods

Floods are among the most common and devastating disasters. Read more about why they happen and their effects.

Right now, there are hundreds of volcanoes actively bubbling away around the world. It is estimated that there are about 1,500 potentially active volcanoes all over the globe (USGS).

When a volcano erupts, it can be devastating for communities living around it. Families often need to evacuate their homes in the wake of an eruption – if it’s serious, buildings and infrastructure can be flattened, leaving people homeless.

Find out more about volcanoes, what they are, how they erupt, and what the possible consequences are for families and communities living around them.

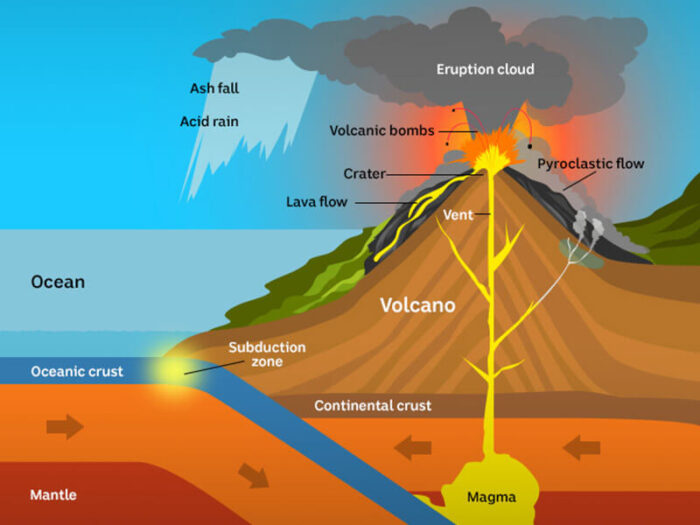

A volcano is a mountain that opens downward to a pool of molten rock below the surface of the earth. This molten rock is known as magma.

When it erupts, huge amounts of very hot gas, boulders, ash and molten rock can burst out. This is thrown into the air, often pouring down the side of the mountain.

When the molten rock pours down the mountain it creates lava or pyroclastic flows. Any buildings or structures surrounding the area of a volcano when it erupts will be destroyed or damaged.

As well as flows of incredibly hot liquid mud and rock, homes are commonly destroyed by hot ash falling like rain on everything below.

There are about 1,500 potentially active volcanoes around the world.

There are over 450 volcanoes situated in the Pacific “Ring of Fire”

The temperature of lava can vary from 700 to 1,200 °C

How does a volcano erupt?

A volcano eruption happens when magma below the surface rises to the top of the mountain, causing gas and bubbles to appear. Pressure from this gas can build so much that a volcano explodes.

How often do volcano eruptions happen?

According to David Pyle, Professor of Earth Sciences at Oxford University, there are about 1,500 volcanoes around the world that are known to have erupted at some point in the past 10,000 years.

Most of these volcanoes could erupt again at some time in the future. In any year, about 60 to 80 volcanoes erupt. Mostly these will be small eruptions.

The majority of volcano eruptions occur along the Pacific Rim, in what is known as the ‘Ring of Fire’. The Ring of Fire is a path along the Pacific Ocean characterised by active volcanoes and frequent earthquakes. 75% of all volcanoes are located along the Ring of Fire.

Most volcanoes are found in lines along the edges of the Earth’s tectonic plates.

In some places, for example in South America, Alaska and eastern Russia, volcanoes form tall mountains that are spaced 40 to 50 kilometres apart and line up parallel to the edge of the continent.

In other places, such as the West Indies, some Pacific islands and parts of Indonesia, volcanoes form islands.

Volcanic eruptions and other extreme events are not ‘natural disasters’.

The term ‘natural disaster’, despite being widely used, is problematic.

Using the word ‘natural’ ignores the role that humans have in the disaster, assuming that the event would happen anyway and there is little that we can do to prevent it.

It’s actually the decisions we make that create a disaster.

Factors like living conditions and poverty, government capacity to prepare and respond, as well as the process of rebuilding and how efficient that would be, are all factors that will define whether a disaster occurs as a result of the natural hazard.

Hazards are inevitable – but the impact they have on society is not.

Read more about the importance of avoiding the term ‘natural disaster’.

Why disasters are not natural

More than half a billion people around the world live in the direct vicinity of a volcano.

Despite the known dangers, people still choose to live in such a high-risk location. But the question is, why?

Thanks to a phenomenon known as ‘upside risk’, the opportunities of living in such a place may offset the known risks.

For farmers, one of the benefits of living near a volcano is the fertile agricultural ground, enhanced by the volcanic ash. This also applies to areas that were covered by volcanic mudflows.

But there are also interesting social reasons for choosing to live in such a high-risk area, with volcanoes shaping the cultural identity of the communities surrounding them.

Although there are benefits to living close to a volcano, families are at also at risk of experiencing health dangers.

Dr Zoe Mildon, a leading expert in the field of Earth Sciences and a lecturer at the University of Plymouth, explains the health risks caused by deadly volcanic eruptions. According to Dr Mildon:

Apart from the obvious health risks, homes and infrastructure are extremely vulnerable when volcanoes erupt. People might lose their home to the disaster, leaving them in urgent need of shelter.

Please donate today to help families who urgently need shelter after volcanoes and other life-changing disasters.

Donate NowShelterBox is always on alert to respond to a volcano eruption, just like any other disaster.

However, extra care needs to be taken when responding to volcano eruptions, due to the dangers and challenges around this type of disaster. We need to make sure the environment is safe for our Response Teams to operate in.

We might send our teams out with additional safety equipment, such as respiratory protection, as the air quality can be affected by volcano eruptions.

As soon as we know the operating environment is safe, we would aim to have a ShelterBox Response Team on the ground.

We asked our Operations team some questions about how to plan for a volcanic eruption and how ShelterBox prepares for such a disaster.

How do scientists and volcanologists monitor volcanoes?

Many of the world’s most active volcanoes are monitored with instruments designed to detect early warning signs: webcams, to detect visual changes around the volcano, or in the volcanic vent; seismometers, to detect earthquakes; and spectrometers to measure changes in gas composition.

Many volcanoes can also be monitored from space, using radar and other instruments to measure changes in the shape of the volcano as pressure builds up below; or to measure changes in volcanic heat and gas.

What are the challenges of responding to a volcanic eruption?

In the aftermath of a volcano eruption, communities often face huge difficulties as the volcano can still be active and monitored. There is sometimes still a lot of seismic activity after a volcano eruption, so communities cannot return to certain areas until it is shown all clear.

Watch the video below to find out what were the challenges faced in Guatemala, after the eruption of the Fuego volcano.

We responded in Guatemala in 2018, after the Fuego volcano erupted.

The challenges for local communities were huge, with some families unable to return home. A major road between communities had been cut by the volcanic flow, which made the challenges even greater.

The authorities were also planning a no-build zone in areas at risk of future eruptions, so for some families this meant that they would never be able to return to their previous locations.

ShelterBox supported families in Guatemala with small tents that were used as safe spaces to give families some privacy and preserve dignity.

Responding in GuatemalaMany thanks to Dr Zoe Mildon, a leading expert in the field of Earth Sciences and a lecturer at the University of Plymouth and to David Pyle, Professor of Earth Sciences at Oxford University.